Discrete element modeling of distal deformation propagation in thrust wedge and Implications for early deformation on Northern Tibetan and Iranian Plateaus (Journal of Structural Geology)

The classical Coulomb critical wedge theory is the fundamental theory for explaining the growth process of thrust wedges (Chapple, 1978; Dahlen, 1990; Davis and Engelder, 1985; Davis et al., 1983). This theory posits that the deformation of a thrust wedge develops sequentially from the hinterland to the foreland, meaning that distal deformation occurs latest. However, increasing geological evidence suggests that the northern Tibetan and Iranian Plateaus, far from the southern collision zones, experienced deformation shortly after the collision of India and Arabia with Eurasia (Fig. 1). Furthermore, although a weak lower crust and distal pre-existing faults (or weak zones) are common, their relationship with early distal deformation remains unclear.

To address the above issues, Dr. Jiankun He, a researcher at the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team, including doctoral student Zhou Chao, Associate Researcher Wang Weimin, Senior Engineer Wang Xinguo, doctoral students Zhao Youjia and Jiang Yong, collaborated with Dr. Hao Su from the School of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China. Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42120104004, 42174112) and the “Second Tibetan Plateau Comprehensive Scientific Expedition and Research Program” (No. 2019QZKK0707), they used ZDEM (Li Changsheng, 2019) to conduct discrete element numerical simulation experiments and perform stress-strain analysis (Morgan, 2015), exploring the relationship between distal pre-existing faults, basal décollement, and early distal deformation propagation.

Discrete element numerical simulation experiments show:

- The presence of pre-existing faults is a necessary condition for the occurrence of early distal deformation;

- Whether distal pre-existing faults deform early depends on the strength of the basal décollement and is independent of the model width; a strong basal décollement cannot activate distal pre-existing faults, whereas a weak basal décollement can cause them to deform early;

- In the case of a weak basal décollement, a slower shortening rate not only facilitates greater shortening absorption by the distal pre-existing fault at the early stage, but also results in a more pronounced deviation from the sequentially-forward deformation propagation.

These findings demonstrate that the preferential deformation of distal pre-existing faults is mechanically controlled by a weak basal décollement layer.Combining geological and geophysical observations, we suggest that the early deformations observed in the northern Tibetan and Iranian Plateaus shortly after the collision of the Arabian and Indian plates with the Eurasian plate are likely the result of the preferential reactivation of pre-existing faults (weak zones) under the influence of a weak lower crust(Zhou et al., 2024)。

Title

Discrete element modeling of distal deformation propagation in thrust wedge and Implications for early deformation on Northern Tibetan and Iranian Plateaus

Authors

Chao Zhou1,2, Jiankun He1,2, Hao Su3, Weimin Wang1, Xinguo Wang1, Youjia Zhao1,2, Yong Jiang1,2

- State Key Laboratory of Tibetan Plateau Earth System, Environment and Resources (TPESER), Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China

- University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

- Laboratory of Seismology and Physics of Earth’s Interior, School of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China

- Correspondence to: Jiankun He (jkhe@itpcas.ac.cn)

Abstract

Coulomb critical wedge theory predicts that thrust wedges would grow sequentially from the hinterland to the foreland, meaning that distal deformation occurs last. However, in the northern Tibetan and Iranian Plateaus, far away from the southern collision zones, widespread deformation occurs soon after collisions of Arabia and India with Eurasia. Additionally, despite the prevalence of weak lower crust and distal pre-existing faults or weak zones, their relationship to early distal deformation remains poorly understood. For this reason, we run systematic experiments of discrete element models involving basal d´ecollement layer as well as distal pre-existing fault. Our model results reveal that (1) the presence of pre-existing faults is necessary for the occurrence of early distal deformation; (2) the early deformation of distal pre-existing fault is dependent on basal d´ecollement strength and independent of model width; (3) strong basal d´ecollement fails to activate the distal pre-existing faults, instead weak basal d´ecollement can deform them at the early stage; (4) in the presence of weak basal d´ecollement, a slower shortening rate not only facilitates greater shortening absorption by the distal pre-existing fault at the early stage but also results in a more pronounced deviation from sequentially-forward deformation propagation. These findings demonstrate that the preferential reactivation deformations of distal pre-existing faults are mechanically controlled by a weak basal d´ecollement layer. Together with geological and geophysical observations, we suggest that the early deformations of northern Tibetan and Iranian Plateaus may be the result of the reactivation of pre-existing faults due to the existence of weak lower crust soon after collisions.

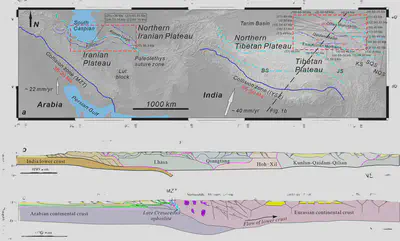

Figure 1. (a) Early deformation superimposed on topographic reliefs at and around the Tibetan and Iranian Plateaus (Tectonic information modified from François et al., 2014; Gao et al., 2013; He and Chéry, 2008; Ye et al., 2021). The locations of collision zones (IYSZ and MZT) are drawn from Yin, 2006 and Su and Zhou, 2020. Sutures are drawn from Robert et al., 2014 and P. Zhang et al., 2022. IYSZ = Indus-Yarlung suture zone, MZT = Main Zagros Thrust, BS = Bangong-Nujiang suture zone, JS = Jinsha suture zone, KS = Kunlun suture zone, SQS = South Qilian suture zone, NQS = Nouth Qilian suture zone, NTP = northern Tibetan Plateau, NIP = northern Iranian Plateau. QTT = Qiman Tagh thrust, NKT = North Kunlun thrust, NQT = North Qaidam thrust. References: (1) He et al., 2018; (2) He et al., 2017a; (3) Y. Wang et al., 2015; (4) An et al., 2020; (5) Chen et al., 2011; (6) F. Wang et al., 2016; (7) G. Wang et al., 2007; (8) A. Wang et al., 2010; (9) Zhuang et al., 2018; (10) J. Zhang et al., 2015; (11) Lin et al., 2019; (12) B. Zhang et al., 2017; (13) X. Wang et al., 2016; (14) Qi et al., 2016; (15) Jian et al., 2018; (16) Du et al., 2018; (17) Cheng et al., 2016; (18) Qi et al., 2015; (19) He et al., 2022; (20) Li et al., 2012; (21) Yin and Harrison, 2000; (22) François et al., 2014; (23) Horton et al., 2008; (24) Rezaeian, 2008; (25) Ballato et al., 2010. (b) Representative N-S structural profile across the Tibetan Plateau (modified by Ding et al., 2022 after Kapp & DeCelles, 2019). (c) Representative N-S structural profile across the Iranian Plateau (after Morley et al., 2009 based on data from Guest et al., 2006b and Ballato et al., 2008 for the Alborz Mountains, from McQuarrie, 2004 for the Zagros Mountains, and from Agard et al., 2005 for the Sanadaj-Sirjan zone).

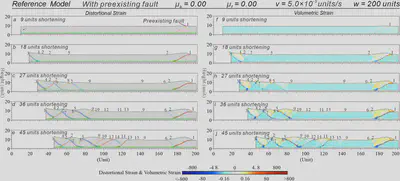

Figure 3. Results of Reference Model with distal pre-existing fault, low friction coefficient of basal décollement μb = 0.00, low friction coefficient of basal décollement μf = 0.00, faster shortening rate v = 5.0 × 10-3 units/s and initial width w = 200 units. (a-e) Sequential results with distortional strains superimposed on the deformed particles. (f-j) Sequential results of volumetric strains. Numbering denotes the initiation sequence of thrusts (same in the following figures).

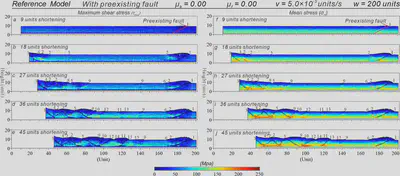

Figure 4. Stress results of Reference Model. (a-e) Maximum shear stress. (f-j) Mean stress.

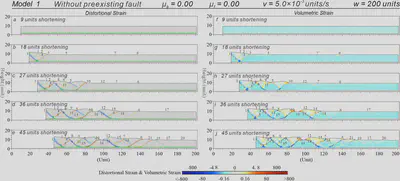

Figure 5. Results of Model 1. (a-e) Sequential results with distortional strains superimposed on the deformed particles. (f-j) Sequential results of volumetric strains.

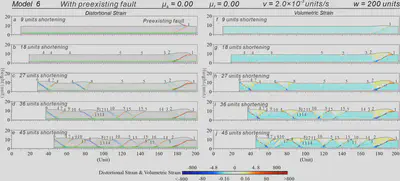

Figure 9. Results of Model 6. (a-e) Sequential results with distortional strains superimposed on the deformed particles. (f-j) Sequential results of volumetric strains.

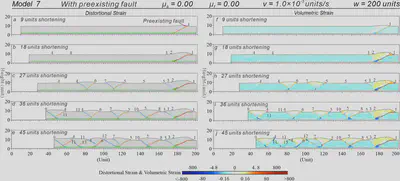

Figure 10. Results of Model 7. (a-e) Sequential results with distortional strains superimposed on the deformed particles. (f-j) Sequential results of volumetric strains.

Acknowledgements

The software used for the simulation experiments was ZDEM (https://geovbox.com/en/), a discrete element numerical simulation software developed by Dr. Chang-Sheng Li. We thank Julia Morgan at Rice University for providing her discrete element code (RICEBAL v5.4) and post-processing scripts and algorithms, which have been used to process and display the model outputs presented in our modeling. We acknowledge Beijing PARATERA Tech CO., Ltd. for providing HPC resources that have contributed to the research results reported in this paper (https://paratera.com/). This paper benefited significantly from the thorough and constructive comments and suggestions by two anonymous reviewers, and Editor Dr. Jianhua Li. This work was jointly supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42120104004 and 42174112), and the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (No. 2019QZKK0708).

References

Due to space limitations, please refer to the detailed references in:Zhou, C., He, J., Su, H., Wang, W., Wang, X., Zhao, Y., Jiang, Y. 2024. Discrete element modeling of distal deformation propagation in thrust wedge and Implications for early deformation on Northern Tibetan and Iranian Plateaus. Journal of Structural Geology, 184, 105150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2024.105150.

Appendix (Experimental Procedure)

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2024.105150.

Translator: Bao Xianjun