Influence of Basal Detachment Strength on the Formation and Evolution of the Southwestern Sichuan Fold-Thrust Belt - Insights from Discrete Element Modeling

The southwestern Sichuan fold-thrust belt (SWSB) is a duplex detachment system with two sets of detachments: a basal Precambrian detachment at a depth of approximately 15–17 km and an upper Mid-Triassic detachment. The SWSB experienced forward-breaking propagation during the Cenozoic. The current dynamic mechanisms controlling the thrusting and the control mechanisms of the two detachments on the structural deformation pattern of the SWSB still require in-depth research. This paper designs three comparable discrete element numerical models. In these models, the shallow detachment has the same parameters, but different mechanical strengths and thicknesses are designed for the basal detachment to explore the influence of different basal detachment strengths on the formation and evolution of the SWSB. Model I is characterized by a strong frictional basal detachment, exhibiting forward-breaking thrusting towards the foreland in both deformation phases. Most deformation and thrust faults are concentrated near the active backwall, accompanied by the development of imbricate structures and two pop-up structures. For the geometric parameters of the wedge on the left side of Model I, it shows the characteristics of “linearly increasing wedge height” and “stepwise increasing wedge width and slope angle”. Model II has a basal detachment thickness of 500 m and moderate friction. In this model, stress and strain propagate rapidly into the foreland, and multiple thrust and back-thrust faults form on the upper detachment during the second compression phase. The deformation process of Model II during the first compression phase is similar to that of Model I. However, in the second compression phase, the wedge reaches a stable state, and its geometry remains unchanged, with deformation propagating along the shallow detachment to the right side of the model. Model III has a larger basal detachment thickness and moderate friction, and the geometry and activity of thrust faults in its foreland are significantly different from the other models. In the second compression phase of this model, two additional pop-up structures are generated. The first half of the first compression phase is similar to the first two models. In the second half of the first compression phase and the second compression phase, the wedge is in a stable state. Notably, all models undergo a transition from a subcritical state to a supercritical state during the first stage of shortening, indicating that deformation is rapidly propagating along the basal detachment towards the right side of the model. Overall, Model III more accurately reflects the deformation characteristics of the SWSB, indicating a strong correlation with the evolution of this region. These models help to understand the deformation process and formation mechanism of the SWSB and can provide a reference for hydrocarbon exploration beneath the shallow detachment. (Wang et al.,2024)。

[Wang Y, Wang L, Ren R, Wei G, Chen Z,Su N and Zhang Y (2023), The influence of basal detachment strength on formation of the southwestern Sichuan fold-thrust belt: insights from discrete-element numerical simulations. Front. Earth Sci. 11:1251417.](https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2023.1251417) #### TitleThe influence of basal detachment strength on formation of the southwestern Sichuan fold-thrust belt: insights from discrete-element numerical simulations

Yanqi Wang, Lining Wang*, Rong Ren, Guoqi Wei, Zhuxin Chen, Nan Su and Yuqing Zhang

Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration and Development, Beijing, China

Introduction:

The southwestern Sichuan fold-thrust belt (SWSB) is a duplex detachment system and features the basal Precambrian detachment at a depth of approximately 15–17 km and the upper Mid-Triassic detachment. Moreover, the SWSB undergoes forward-breaking propagation during the Cenozoic. To date, the mechanism and kinematic evolution governing the SWSB in this thrusting deformation as well as the way the two detachments control the structural deformation pattern of the SWSB remains unknown.

Methods:

In this work, three discrete-element numerical models with the same strong upper detachment but basal detachments with different mechanical strengths and thicknesses were designed to study the deformation of the SWSB.

Results:

The results indicate that for the Model I with a strong frictional basal detachment with thickness of 500 m, most deformation and thrust faults concentrate near the mobile backwall. Model I exhibits characteristics such as linearly increasing wedge height and stepwise increasing wedge width and slope angle. For the Model II with a modest frictional basal detachment with thickness of 500 m, the strain and deformation propagate into the foreland quickly and multiple back-thrust and thrust faults form on the upper detachment in the second thrusting period. The first thrusting period in Model II, exhibits similarities with Model I. However, in the second period, the wedge reaches a stable state, and its geometry remains constant. In this stage, the deformation propagates along the shallow detachment into the right side of the model. The geometry and activity of thrust faults in the foreland differ significantly in the model III with a modest frictional basal detachment but a greater thickness. Two additional pop-up structures are generated in the second period in this model. The first half of the first thrusting period is similar to the first two models. In the second half of the first period and the second period, the wedge is in a stable state. In the first stage of the shortening, all models undergo a transition from a subcritical state to entering a supercritical state, which indicates that the deformation is progressing rapidly along the basal detachment towards the right side of the model.

Discussion:

The results of Model III are consistent with the deformation pattern of the SWSB. The study of the kinematics and interaction between two detachments could help hydrocarbon exploration beneath the upper detachment.

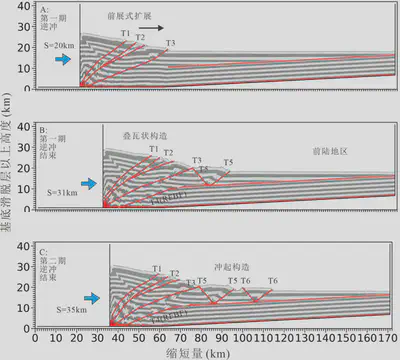

Deformation process of Model I (basal detachment thickness of 500 m, friction coefficient of 0.3) (A)-(C) show the results of Model I at shortening (S) of 20 km, 31 km, and 35 km, respectively. T1-T6 represent thrust faults numbered according to their formation sequence.

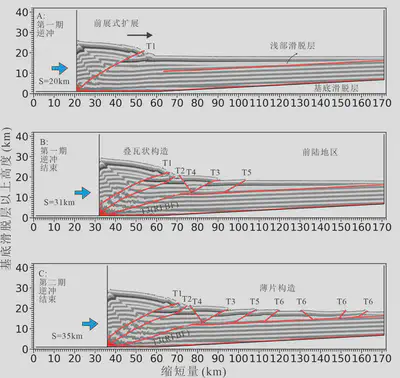

Deformation process of Model II (basal detachment thickness of 500 m, friction coefficient of 0.2) (A)-(C) show the results of Model II at shortening (S) of 20 km, 31 km, and 35 km, respectively. T1-T6 represent thrust faults numbered according to their formation sequence.

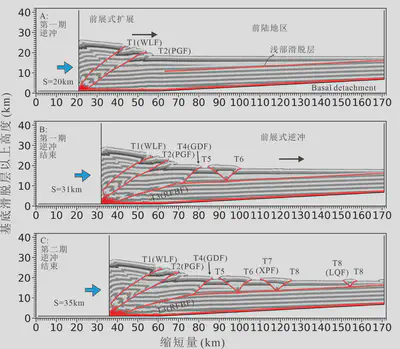

Deformation process of Model III (basal detachment thickness of 1,000 m, friction coefficient of 0.2)(A)-(C) show the results of Model III at shortening (S) of 20 km, 31 km, and 35 km, respectively. T1-T8 represent thrust faults numbered according to their formation sequence.

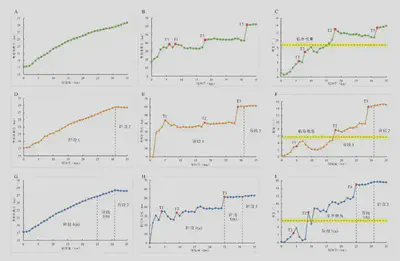

Quantitative analysis diagrams of Models I, II, and III during compression. (A), (D), and (G) show the variation of wedge height with shortening for Models I, II, and III, respectively; (B), (E), and (H) show the variation of wedge width with shortening for Models I, II, and III, respectively; (C), (F), and (I) show the variation of slope angle with shortening for Models I, II, and III, respectively.

Translator: Bao Xianjun