Influence of Surface Processes on Strain Localization and Seismic Activity in the Longmen Shan Fold-and-Thrust Belt:Insights From Discrete-Element Modeling(Tectonics)

Download the VBOX (ZDEM) experiment scripts in this article.: The code for our DEM experiments can be obtained from Open Science Framework (Model I-1, no surface processes, https://osf.io/tz2qg; > Model I-2, with surface processes, https://osf.io/pa9sy).

Wang, M., Wang, M., Feng, W., Yan, B., & Jia, D. (2022). Influence of surface processes on strain localization and seismic activity in the Longmen Shan fold-and-thrust belt: Insights from discrete-element modeling. Tectonics, 41, e2022TC007515. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022TC007515

Title

Influence of Surface Processes on Strain Localization and Seismic Activity in the Longmen Shan Fold-and-Thrust Belt: Insights From Discrete-Element Modeling

Authors

Maomao Wang1,Ming Wang1,Wang Feng1,Bing Yan1,Dong Jia2

- Institute of Tectonics and Geophysics, College of Oceanography, Hohai University, Nanjing, China

- School of Earth Sciences and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

Abstract

We investigated interactions between structural deformation and surface processes in the Longmen Shan fold-and-thrust belt and the adjacent western Sichuan foreland basin (WSFB) in the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. The discrete-element modeling (DEM) method was used to study the influences of the various mechanical properties of the detachments and syn-tectonic erosion/deposition on the structural evolution of the Longmen Shan and WSFB. DEM simulations demonstrated two stages of surface processes during the Late Cenozoic profoundly influenced thrusting sequences and strain localization in the hinterland and foreland portions of the Longmen Shan. Models indicate that the fold-and-thrust belt lacking surface processes propagate in a forward-breaking manner, whereas those with surface processes develop following an out-of-sequence thrusting pattern. We infer that large-scale erosion propagation from the Sichuan Basin westward to the Tibetan Plateau since Late Cenozoic caused the Longmen Shan hinterland to reach a subcritical wedge state. Tectonic activity retreats to the edge of Plateau, enhancing the rapid uplift of the Longmen Shan and inhibiting the propagation of substantial shortening deformation to the foreland basin. The foreland thrust belt slides stably along the shallow detachment, causing the initiation and growth of the Longquan fault in the leading front. These results explain why both the Longmen Shan hinterland and the western Sichuan foreland thrust belts are currently in a state of simultaneous seismic activity. Our findings offer important implications regarding the seismic potentials of other fold-and-thrust belts that interact with dynamic surface processes.

Figure 1. Geological map of the eastern Tibetan Plateau showing the focal mechanisms of the 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake, the 2013 Mw 6.6 Lushan earthquake, and the 2020 Ms 5.1 Qingbaijiang earthquake. The red lines represent surface ruptures of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake ([Liu-Zeng et al., 2009](#refer-Liu-Zeng2009); [Xu et al., 2009](#refer-Xu2009)). The gray rectangles represent the age of previous published low-temperature thermochronology data, from ([E. Wang et al., 2012](#refer-Wang2012) )[1] and ([Richardson et al., 2008](#refer-Richardson2008))[2]. The brown lines represent the structural profiles in the study area, where profile (a–c) is shown in Figures 5a–5c, respectively. LQF: Longquan Fault; PGT: Pengguan Thrust; RFBT: Range Front Blind Thrust; WLF, Wulong Thrust; WLT: Wenchuan–Maowen Fault; XPT: Xiongpo Thrust; YBT: Yingxiu–Beichuan Thrust.

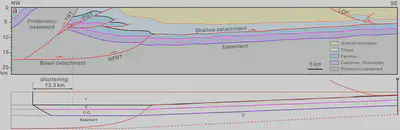

Figure 6. (a) Representative structural profile a (see location in Figure 1) in the central segment of the Longmen Shan fold-and-thrust belt (Jia et al., 2010). (b) Restoration results of deformed horizons in foreland region of structural profile (a) The shortening of the base of Jurassic layer in foreland region is 13.3 km. The Cenozoic sedimentary strata within hinterland of the Longmen Shan in this profile are absent.

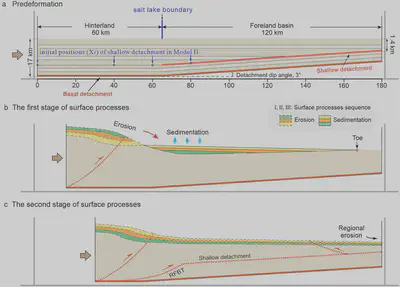

Figure 8. Schematic representation of the experimental setup. (a) The initial model setup contained two-level detachments with differential mechanical strengths. (b) When simulating the surface processes in the first stage of Model I-2, the eroded materials from the hinterland were deposited sequentially in the foreland. c) When simulating the surface processes in the second stage of Model I-2, surface erosion occurred throughout the wedge, and materials were transported from the system. The stages of b and c of Model I-2 are not to scale.

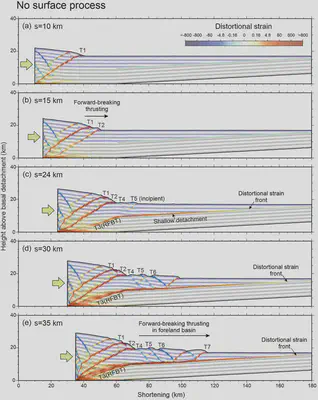

Figure 9. The progressive evolution observed in Model I-1 (conducted with five stages and no surface processes), with distortional strains superimposed on the colored strata. (a)–(e) The results of Model I-1 at total shortenings of 10 km (a), 15 km (b), 24 km (c), 30 km (d), or 35 km (e). T1–T7 denote thrust faults in the order of their formation. RFBT, Range Front blind thrust.

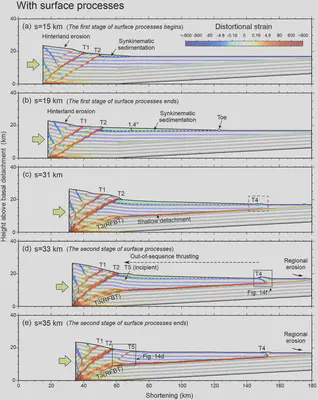

Figure 10. The progressive evolution observed in Model I-2 (conducted with five stages and surface processes), with distortional strains superimposed on the colored strata. (a)–(e) The results of Model I-2 at total shortenings of 15 km (a), 19 km (b), 31 km (c), 33 km (d), or 35 km (e). T1–T5 denote thrust faults in the order of their formation.

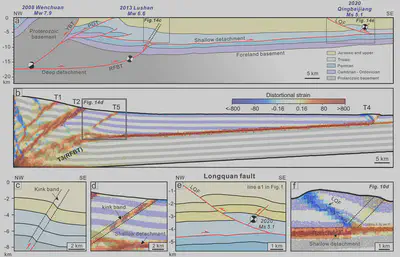

Figure 14. Comparison between the structural cross-section of the central Longmen Shan thrust belt and the results of Model I-2 (simulated with surface processes). (a) Structural profiles of the central Longmen Shan (modified from Jia et al., 2010) and the locations of the 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake, the 2013 Mw 6.6 Lushan earthquake, and the 2020 Ms 5.1 Qingbaijiang earthquake. (b, c) Comparison of the structural profile and range front structure in Model I-2. (d, e) Comparison of the structural profile and foreland thrust belt in Model I-2. LQF, Longquan Fault. The location of (e) is shown in structural profile a1 in Figure 1.

Conclusions

Based on DEM simulations, we reveal the interaction between thrusting propagation and surface processes, and its influence on modern seismicity in the Longmen Shan fold-and-thrust belt and its adjacent WSFB. Based on our study results, we obtain the following conclusions:

DEM simulations without surface processes indicated that the fold-and-thrust belt developed in an in-sequence thrusting manner. In contrast, DEM simulations with surface processes revealed that the Longmen Shan fold-and-thrust belt developed in an out-of-sequence manner during the late Cenozoic. Starting at ∼30–20 Ma, rapid denudation processes occurred in the Longmen Shan hinterland, and the YBT and PGT Faults continued to be active. From ∼10 Ma to the present, large-scale propagation of denudation occurred from the Sichuan Basin toward the Tibetan Plateau, and tectonic activity retreated to the hinterland of Longmen Shan. Surface processes were relatively quiescent between these two stages, structural shortening propagated forward through the RFBT, and formed the Longquan Fault in the Sichuan basin.

Instrumental and historical earthquakes indicate that the frontal faults in the WSFB and the imbricate faults in the Longmen Shan hinterland region are simultaneously seismically active. We interpret that the activity of the Coulomb wedge of the Longmen Shan is related to the latest stage of surface process. Since ∼10 Ma, large and widespread propagation of erosion from the Sichuan Basin toward the eastern Tibet Plateau caused the Longmen Shan hinterland to enter a subcritical state. The reactivation of reverse faults in the hinterland enhanced the rapid uplift of the Longmen Shan and inhibited most of its slip lateral propagation to the foreland basin. The WSFB is currently in a critical state, with wedge slides occurring steadily along the shallow detachment, with the occurrence of frequent, small-moderate earthquakes in the frontal thrust.

The distribution of Mesozoic salt lakes in the interior of the Sichuan Basin influenced the location, rate, and structural style of thrust slip that propagated from the Longmen Shan hinterland to the foreland basin. Our simulations indicate that the front blind thrust of Longmen Shan range gradually connects the basal detachment and shallow detachment in foreland, and its position is controlled by the western boundary of the salt-lake. Results of comparative experiments show that fault slips from the hinterland of Longmen Shan entered the southwestern Sichuan basin extensively to form several thrust fault-related folds above shallow detachment. However, slip in the northern Longmen Shan was confined to the range front and did not propagate into the northwest Sichuan basin. This suggests that the structural variability along the strike in the Longmen Shan can be explained from the perspective of the internal factors of the Sichuan basin.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFC3000604) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42172232, 41702202, and 41927802). Numerical simulations were performed on the discrete element modeling software VBOX (www.geovbox.com). The authors thank Julia Morgan (Rice University) for generously sharing her discrete element code (RICEBAL v5.4) and post-processing scripts and algorithms, which have been used to process and display the model outputs presented in our modeling. The authors thank Dr. Chang-Sheng Li (East China University of Technology) for his suggestions in the numerical simulations. The numerical simulation of this study is performed on the computing facilities in the High-Performance Computing Center (HPCC) of Nanjing University. The authors thank Jonny Wu and Sharadha Sathiakumar for their constructive reviews.

Data Availability Statement

The authors used VBOX version 2.1 (C. Li et al., 2021; https://geovbox.com/en/) for the discrete-element method (DEM) numerical simulations. Numerical simulations were conducted at the High-Performance Computing Center (HPCC), Nanjing University. The code for our DEM experiments can be obtained from Open Science Framework (Model I-1, no surface processes, https://osf.io/tz2qg; Model I-2, with surface processes, https://osf.io/pa9sy).

References

Li Changsheng, 2019. Quantitative Analysis and Simulation of Structural Deformation in Fold-Thrust Belts Based on Discrete Element Method. Doctoral Dissertation. Nanjing: Nanjing University. Liu-Zeng, J., Zhang, Z., Wen, L., Tapponnier, P., Sun, J., Xing, X., et al. (2009). Co-seismic ruptures of the 12 May 2008, Ms 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake, Sichuan: East–west crustal shortening on oblique, parallel thrusts along the eastern edge of Tibet. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 286, 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.017 Xu, X., Wen, X., Yu, G., Chen, G., Klinger, Y., Hubbard, J., & Shaw, J. (2009). Coseismic reverse- and oblique-slip surface faulting generated by the 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake, China. Geology, 37, 515–518. https://doi.org/10.1130/G25462A.1 Wang, E., Kirby, E., Furlong, K. P., Van Soest, M., Xu, G., Shi, X., et al. (2012). Two-phase growth of high topography in eastern Tibet during the Cenozoic. Nature Geoscience, 5, 640–645. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1538 Richardson, N. J., Densmore, A. L., Seward, D., Fowler, A., Wipf, M., Ellis, M. A., et al. (2008). Extraordinary denudation in the Sichuan Basin: Insights from low-temperature thermochronology adjacent to the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Geophysical Research, 113, B04409. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004739Translator: Bao Xianjun